More than 20 million people—about 15% of the United States workforce—work for a local, state, or federal government entity. A majority of these work in local government (e.g., schools, police and fire departments, county social service agencies), about a third in state government (e.g., universities, tax bureaus, state hospitals), and the remainder in federal government (e.g., post offices, national parks). Millions more work for private employers who receive most or all of their funding from public contracts or grants.

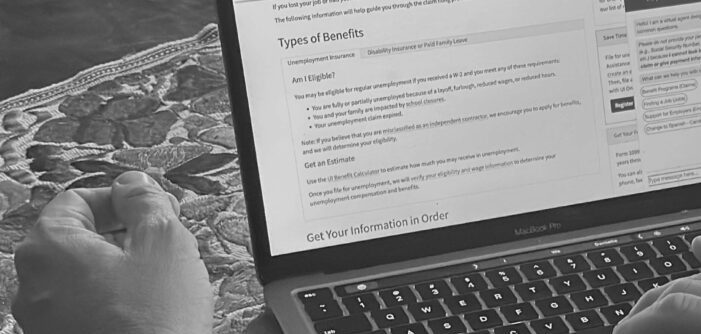

With the exception of the military, government has been generally slower to adopt technology than the private sector. Reasons for this include lack of funding, higher public scrutiny, complex contracting processes, lack of internal IT capacity, and agency fragmentation. The slow pace of technology adoption in some cases has led to both costly and cumbersome service provision; the vision of digital government outlined by federal policymakers in the 1990s has yet to be realized. Greater use of technology by governments holds a lot of promise for both workers and the public: it can remove some of the time-consuming and glitchy processes that frustrate everyone, allow workers to focus on the complexity inherent in providing public services, make government more accessible to more people, and get assistance more quickly into the hands of people who need it.

But there are reasons to be attentive to how technologies are rolled out, especially as the recent jump in technology funding opens up the floodgates of consultants and contractors pitching their products. Technology cannot be used to paper over the lack of investment in the public sector that has characterized the past two decades. In fact, technology presents the greatest risk when it’s simply layered on top of already overwhelmed workers and processes, because there is no capacity built in for evaluation and recalibration to ensure that the technology is working as intended. Within the public sector there is enormous variation in size, resource capacity, mission, and political and social context, all of which affect whether and how technology is implemented. But nearly all public sector employers have spent the past decades watching revenues fail to keep up with the costs of providing government services. Since 2008, public sector employment has been stagnant or declining, while private sector employment has grown by 12% and the U.S. population—a measure of demand for government services—by nearly 7%.

Some technologies also present inherent risks, such as those intended to replace or supplement human decision-making. Research suggests that people are reluctant to make different decisions than those suggested by analytics designed to supplement human decision-making, sometimes leading to worse outcomes than those the technology was intended to remediate. There has been considerable evidence that advanced technologies can replicate or even exacerbate racial and ethnic biases. Governments should be deliberate and cautious as they adopt such technologies. Involving workers in the scoping, design, implementation, and evaluation of advanced technologies in particular can help safeguard public trust. Technology as a cost-saving measure must be implemented within a framework that recognizes the role public workers play in assessing whether systems are serving the people the programs are intended to serve.